Language family

Contents

Translations

famiglia linguistica | famille linguistique/famille de langues | Sprachfamilie

Article

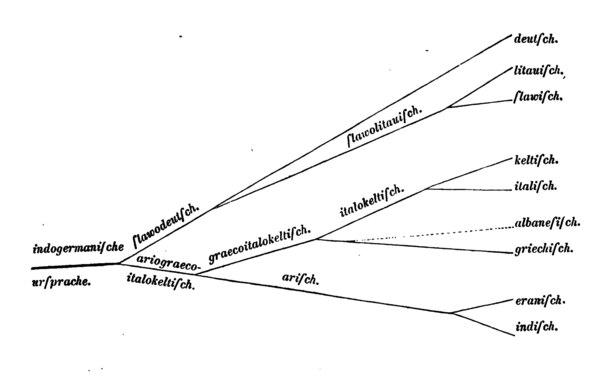

A language family is a group of languages identified on a genealogical (or genetic) basis. The genealogical criterion has been scientifically established during the 19th century and constitutes a core notion in the historical linguistics. Its main output is the tree model (Germ. Stammbaumtheorie) presented in 1861 by August Schleicher, although it had been announced by Schleicher in a series of papers since 1853. Schleicher’s tree model is the visual representation of the relationships existing between languages within the Indo-European group. However, rather than being a simple descriptive model, it has a great euristic value: it is in fact the result of the historical-comparative method applied to a group of languages for which the linguistic family relationship has been established. In other words, by means of the historical-comparative method (see also sound law), it is possible to establish the existence of cognate linguistic forms and consequently to trace the languages that exhibit such forms back to an original proto-language from which they have been generated over time.

Schleicher’s first tree model (1853) put at the top the common ancestor, Indo-European, (Indogermanisch in the German terminological tradition), divided into three branches: (1) Celtic; (2) Slavic-Germanic divided into Germanic and Baltoslavic, the latter in turn divided into Baltic and Slavic; (3) Ario-Pelasgic divided into Pelasgic (Latin and Greek) and Arian (Iranic and Indic).

Schleicher's tree from Wikimedia Commons.

In contrast, the model presented later (1861), generally regarded as definitive, is presented horizontally and has a more complex – always binary – articulation: on the left side there is the protolanguage, on the right side the ramifications and later developments, each time divided into two subgroups: 1) Slavic-Balto-Germanic subdivided into Germanic (historically represented by northern and western Germanic, as well as the extinct Gothic) and Balto-Slavic subdivided into Baltic (Old Prussian, Lithuanian/Latvian) and Slavonic (western and southeastern); 2) Aryo-Greek-Italo-Celtic subdivided into Celtic (Gaelic languages, British languages, extinct Gallic), Italic subdivided into Latin (Romance languages) and extinct Osco-Umbrian – or Sabellic, and finally Albanian from which the branches of Ancient Greek (which will give rise to Modern Greek) and Indo-Iranic (Iranian languages, Indic languages) is detached.

A major difference between the two versions of the theory lies in the position of Celtic: further studies have shown that Schleicher had the right intuition in 1853 by separating Celtic from Italic. In fact on the existence of an Italo-Celtic subgroup the debate has long been heated. Proponents rely on certain correspondences, e.g., the ending in -r of the passive, that indeed unite the Celtic and Italic groups. However, a morphological correspondence may also have motivations other than a common Indo-European origin: it could in fact be a common innovation, or a coincidental parallel innovation, or even a phenomenon of language contact, as is precisely the case with the -r ending of the passive for the languages of the Italic and Celtic groups.

Since Watkins’s article (Italo-Celtic revisited, 1966), most scholars agree that the Italo-Celtic group is not adequately documented: among others, MacCone (Relative Chronologie: Keltisch, 1992) has demonstrated the non-existence of a common proto-Italo-Celtic by explaining the common traits between the two groups from the frequent contacts between the Celtic and Italic populations of the origins. And this is the most widely accepted hypothesis among scholars today. However, there still remain some supporters of this hypothesis (see, e.g., Kortlandt, Italo-Celtic Origins and Prehistoric Development of the Irish Language, 2007) who see not only in the language, but also in the archaeological record, the actual evidence for the existence of a common proto-language of origin.

New linguistic data further expanded the tree model: the decipherment of Hittite (Hrozný 1915, 1917) and its consequent identification as an Indo-European language led to the addition of the entire Anatolian language group. Then, the seminal work of Ventris and Chadwick (1953) marked the definitive recognition of the Mycenaean, the language encoded in Linear B, as Greek of 2nd millennium, anticipating by many centuries the attestations of the Greek group. Moreover, in early 20th century, Tocharian as the most Eastern IE languages has been discovered and identified.

Subsequent expansions prove that Schleicher’s tree model of Indo-European languages should not be regarded as a definitive model in itself. Nonetheless the methodology at its basis – precisely the historical-comparative method – still remains unchallenged and has been (more or less successfully) employed in order to found other language families of the world, e.g., the Afro-Asiatic family, the Sino-Tibetan family etc.

Example

While Indo-European remains the prototypical example of a language family, several details about internal branching may vary significantly in the works of different scholars.

Other examples of language families from the Ancient Near Easter world include the Afro-Asiatic family, with the all-important Semitic Branch (to which Akkadian, Eblaite, Aramaic, Arabic, Canaanite etc. all belong), which is as complex and debated as the Indo-European one, but also the Hurro-Urartian language family, which to date only includes to members. Other languages of the Ancient Near Eastern Areas are, instead, isolated, meaning that no genealogical relationship was established so far.

References

Anthony, David W. and Ringe, Don (2015). The Indo-European Homeland from Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives. Annual Review of Linguistics 1, pp. 199–219. Barbera, Emanuele, Corso di Linguistica Generale. http://www.bmanuel.org/corling/corling2-0.html Cotticelli-Kurras, Paola (2007). Lessico di linguistica. Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orso. Cotticelli-Kurras, Paola (2009). La ricostruzione della protolingua indoeuropea alla luce dei dati anatolici. Incontri Linguistici 32, pp. 117–136. Graffi, Giorgio. Due secoli di pensiero linguistico. Dai primi dell’Ottocento a oggi. Roma: Carocci, 2010